Revisited - license to learn nr. 2022/10 – ‘Winter is coming’ – fly another day!

Winter time is just a small step away again and we already had a sneak preview of what cold weather can have in store for us. The weather conditions are slowly changing and that brings along the usual – and for some pilots - new challenges. In wintertime you can have the best flying days of the year, but also the worst. From cold, crispy and beautiful weather with amazing views and great working condition for your engine, up to days with snow, ice and cold and nasty weather; the difference between a ‘walk in the park’ and a challenge, or even a ‘no go’. So let’s revisit last year’s license to learn no. 2022-10 in which to find tips on preparing yourself and your aircraft for the most common winter challenges. Remember that a good flight starts by being prepared for the worst! Don’t you agree?

First I will mention 15 ´things to consider´ (A), a not exhaustive list of general aviation do’s and don’t’s in cold weather. After that I will cover 2 more specific topics concerning ‘CO-detection’ (B) en ‘Flight over water’ (C). Hopefully this provides you with a beneficial refresher to be ready for this winter season.

A. Icing: things to consider.

While you may have a well developed flight routine, it’s never a waste of time to refresh your memory for cold weather operations. It’s just ‘good airmanship’.

Here are pointers that can help you prepare mentally.

1. Dress for pre-flight. Ensure you wear warm clothing for the preflight check (gloves, boots, (and if needed) a cap). When doing the outside inspection, you should not feel rushed by cold weather and staying warm will keep you focussed on the tasks at hand.

Remember that extra clothing means extra weight so add around 5 kg per person to the mass and balance calculation!

2. Take extra time for a thorough walk-around. When possible, inspect your aircraft in a heated hangar. That’s the best option for you ánd your aircraft. Move your aircraft out of the hangar when your ready to start your flight. Preferably not sooner, because there’s no use to roll your aircraft out of the hangar and then go back inside for coffee, preparing your flight, or brief your student. I understand you want to be warm, but so does your aircraft. The same goes for the other aircraft in the hanger. When pulling them out of hangar to get to your aircraft, push them all back into the hangar again when they will not be used. And at last: close the hangar doors! It will save warmth - which is expensive at the moment(!) – and, most important, needed to keep all the other aircraft above freezing level.

3. If the aircraft is not parked in a hangar but outside in the shadow, moving it into the sunlight will melt small amounts of frost on the wings and clear the windows. Ensure that the controls are free of any water that could refreeze. If there is still mist around, check that new frost is not forming. It may be advisable not to fly in that case and wait until the weather improves. And – if you decide not to start your flight after all - put the cover back on to prevent frost from forming on the surfaces. If the aircraft is not used regularly, the cover should be removed from time to time to allow any moisture to dissipate and the inside of the cover to dry out.

4. Make sure that all covers (air intakes, pitot system, etc) are taken off when doing your (final) walk around, even when it is cold and you are anxious to start up the aircraft to warm up the engine.

5. If an aircraft is parked outside and icing has formed or it is covered with snow, use a soft brush to wipe the aircraft clean.

Beware:

- Don’t scratch the aircraft when brushing too vigorously!

- Don’t ever use a ice scraper for cleaning the windows!

All aircraft frost, ice or snow must be removed from the aircraft before flight. Even a very light film of frost may reduce lift by as much as 30% and increase drag by 40%.

6. The battery condition may be reduced in cold weather so avoid running the electrics from the battery for any significant time before start.

Beware:

- If the battery is weak or flat: don’t use external power. It is not allowed to start up the engine using external power (caution page 4-6, Supplement POH).

7. Inspect the fuel system for water and ice contamination before each flight. Water in the system can freeze and block the fuel flow. It can also rupture fuel lines and components. Also keep fuel tanks filled as much as possible/as applicable to avoid condensation build-up.

8. After you made an overnight stay away from Rotterdam airport, de-icing fluid can be used. Before using de-icing fluid, make sure it is usable for your aircraft. There are also de-icing fluids - which are intended for larger aircraft - that have a thicker consistency and will not disperse correctly from the wings at our takeoff speeds (55-60kts). Beware that the fluids used will only stop new precipitation freezing on the aircraft for a very short period of time, if at all. Reading the technical data will help! It is a good idea – when you make an overnight trip – to consider the weather forecast and bring any de-icing equipment with you. Ask the ‘balie’ for de-icing fluid and read the technical label before using it. Take a soft cloth along and allow extra time for ice removal when needed. If you don’t clean your cockpit window properly, you pose a safety risk to yourself and to others when you taxi to start your flight. Especially when the sunlight starts hitting your window!

9. It is possible to remove frost and ice with warm water but be very careful to ensure the aircraft is dried afterwards and check no water has found its way into control hinges or other places where it could refreeze and cause issues in the air. Letting the sun do its work is the cheapest and easiest option.

10. Fuel injected engines do not suffer from carburettor icing, but it is still possible for ice to build up air intakes and/or block the engine air filter. The ‘alternate air’ selector, that bypasses the filter, should be checked for proper function.

11. Weather and routing (ceiling, visibility, OAT). The weather may vary along the routing you planned, so it’s important to get as much information about the weather as possible. Mist, low clouds, and low temperatures, can form an obstacle and you have to make sure to always have a planned way out of harms way. And if jou don’t have such an alternative plan, there’s absolutely no shame in calling off the whole flight. Better safe than sorry and fly another day!

12. The landscape for VFR navigation might be totally different to what you’re used to in the summer. Especially if this is the first time you see this winter wonderland from above. Lots of features on the ground change colour or might not be as easy to see. Flying with a more advanced buddy will help you get the needed experience. That’s better than to face the possibility of getting lost on your own!

13. The weather condition at local aerodromes may vary, especially in wintertime. The best way to find out what the local conditions are is just to make a phone call ahead. If the local aerodrome manager advises you not to fly over there due to the foreseen weather – don’t do it.

14. If you’re flying and suddenly experience severe icing buiding up, anticipate control difficulties. Inform ATC and consider declaring an emergency call, depending on how severe the situation is. Keep the aircraft’s speed as high as possible – the stall speed will have increased, but you will not know by how much. The stall warning may have frozen and no longer function. If you suspect propellor icing, cycling the RPM up and then down again may shed some ice. If you can see excessive ice on the wings, there will almost certainly be even more on the tail. This will reduce elevator authority and make the aircraft heavier in pitch. You may need to descend to maintain a safe airspeed. Make a precautionary landing if needed. A good flight is one you can walk away from. Remember that!

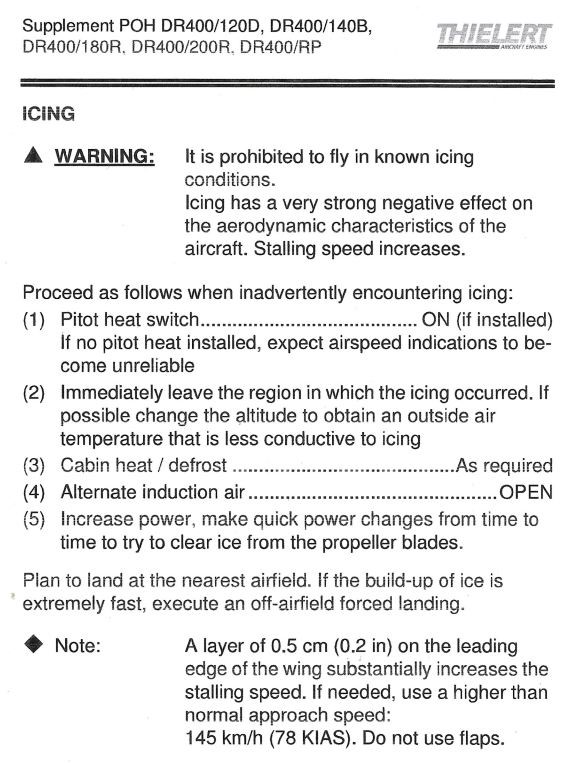

Last, but not least, please take a close look what the DR400 flight manual (Supplement POH 400/140B) says about inadvertent flight in icing conditions:

15. After your flight, clean the aircraft if necessary - mud and slush may dry or freeze and subsequently be harder to remove. Dirt on the underside may cause a reduction in performance. Inspect the wheels and brakes to ensure that they are free of contamination. The next pilot may not appreciate finding the brakes frozen with mud. If there is significant water on the wings, wipe it off. If left overnight on a navigation trip it may freeze, leaving the aircraft covered in ice the next day. Reinstall weather-protection devices such as control locks and pitot covers (ensure the probe is cool so that it does not melt the cover) and tie down the aircraft or make sure that it is warm in the hangar, ready for the first flight the next morning.

B. Cabin heating: enjoyable! What can go wrong?

Have you ever seen this card in your aicraft and do you know what it is there for?

|

Foto: Chemical spot detector |

Yes? I advise you to read further to refresh.

No? I will inform you right away.

Carbon Monoxide-detector: do not poison yourself.

Your cabin heating system is made for pilot and passengers to staying warm when the outside air temperatures are low. Beware however of the hazard of carbon monoxide poisoning! Carbon monoxide (CO) is odourless and tasteless. It is produced by incomplete combustion of fuel and – if inhaled - it enters the bloodstream and mixes with haemoglobin (the part of red blood cells that carry oxygen around your body) to form carboxyhaemoglobin. When this happens, the blood loses its ability to carry oxygen, causing cells to fail and die - effectively producing the effects of hypoxia – felt as a headache, drowsiness, or dizziness.

Other symptoms can include impaired vision, feeling sick, tiredness and confusion, stomach pain, shortness of breath and difficulty breathing. It can eventually cause death. Recovery from a milder form of CO-poisoning can take up to 24 hours.

Fumes escaping through manifold cracks and seals is one of the main sources of such poisoning in light aircraft heaters. That’s why they are frequently checked by maintenance and a CO-detector is placed inside the cockpit. Now you know.

Immediate action: The immediate remedial action is to shut off the heater, open the air vents and, if necessary, land. If the symptoms are severe, or continue after landing, it’s best to seek medical treatment.

C. Flights over water in low temperatures.

And now fort he last topic of today. Please hang in there and continue reading.

If conducting a flight over an extensive stretch of water, make sure to know that in wintertime the water temperature – if you get out of your aircraft - may be hardly survivable. Crossing the channel - for instance - without proper survival equipment can be deadly when your engine stops and you have to ditch the aircraft.

So take at least the following precautions:

1. Fly as high as possible, this will give you more time if ditching is imminent and may allow you to get closer to land. Radio reception will also be better. Consider taking a longer route to avoid exposure to a long water crossing. And as you approach a water crossing, check the engine instruments to ensure everything is normal.

2. A survival or immersion suit designed for aviation use will significantly improve survival prospects in cold waters. Whilst some pilots may feel that this level of protection is ‘over the top’ for a X-channel flight, there have been cases where lives have been saved by the wearing of such clothing, particularly during periods of lower sea temperatures. If the survival suit used is an uninsulated ‘dry suit’, it will keep the water out, but to be fully effective from the cold you will need to wear warm clothing underneath to create layers of air that trap your body heat. Even if you carry a raft, it may be lost or damaged in the ditching. Experience has shown that it is often difficult to enter a raft during high winds and heavy swell. The raft may also be lost or damaged in the impact, so wearing a survival suit is still a wise precaution.

3. If a survival suit is not worn, high insulation clothing which traps air can still improve chances of survival in the water. Woollen clothing may be cumbersome when wet, but it retains around 50% of its insulating properties compared to wet cotton which is only 10% of its dry insulation. Warm headwear will prevent body heat escaping from your head.

4. Part-NCO contains equipment requirements for flight over water. Lifejackets for all onboard are required when in an aircraft beyond gliding range of land, or if in the opinion of the pilot in command, the planned flight path during takeoff or landing is near water, such that a ditching may occur in the event of an emergency.

5. When flying more than 30 minutes or 50 NM from land (whichever is less), the pilot in command is required to assess the survival equipment necessary to carrying on the flight. Such an assessment should consider the sea state and temperature, weather conditions, distance from land and the availability of search and research services. Equipment that may be deemed necessary could include distress signals, such as lights or flares, life rafts for all persons onboard and any life-saving equipment such as drinking water or first aid kits.

6. You may have all the right equipment, but you need to know how to use it effectively and brief all occupants on what to do in the event of ditching. The equipment also needs to be serviceable and accessible for use.

For flights over water also cover:

- Use of lifejackets, including to only inflate once outside the aircraft;

- Location and use of the life raft. Allocate someone to be responsible for taking the life raft from the aircraft in a ditching;

- Use of the ELT, (although normally it operates);

- Preparation for impact, such as brace position, tightening seatbelts, removing headsets and stowing eyeglasses;

Should the worst happen, remember to keep flying the aircraft. Aviate, Navigate and Communicate, in that order.

7. Keeping your seatbelt fastened after the initial impact may allow you to apply more force to open the doors and windows. The shock of cold water may adversely affect everyone’s actions. Therefore, a pre-flight passenger briefing which emphasises interior reference points and the agreed order in which to vacate the aircraft is vital. Do not inflate lifejackets inside the aircraft, inflate them as soon as you are outside.

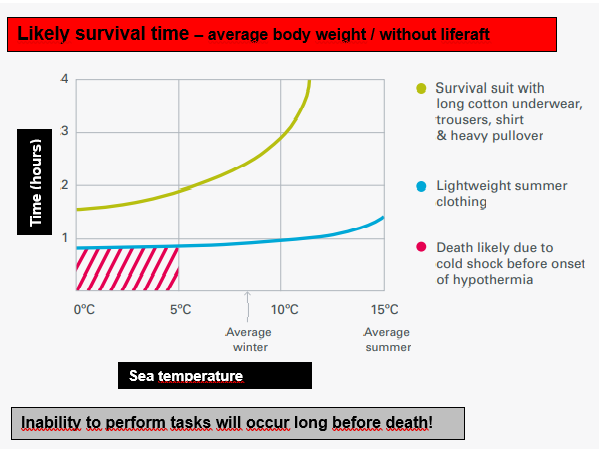

8. Likely survival time. In low sea temperatures, cold shock can cause drowning and sometimes heart failure. This can happen in a matter of minutes. Cold shock may cause a gasp reflex, hyperventilation and an increase in blood pressure. These responses will likely diminish after several minutes if the head can be kept above water and breathing can be controlled. Drowning can also be caused by ‘swimming failure’, whereby the body’s reaction to the cold water is to restrict blood flow to the extremities. Even strong swimmers will lose the ability to move their limbs effectively after a short period of time and the swimming action will become inefficient. This can result in the body adopting a more vertical position in the water, at which point the swimmer may panic and sink. If in cold water for an extended period, the main threat is hypothermia caused by a decrease in body core temperature. Contact with cold water is usually unavoidable when ditching and the effect can be mitigated by wearing a survival suit. Removing yourself from the water and into a life raft will significantly extend the period before hypothermia sets in, but it may not be possible if the body has already succumbed to cold shock.

Please read the diagram below for survivabilty based on water temperature and protective clothing worn.

Let’s wrap things up.

I think the pointers above give you an idea of how serious I take flying over fast stretches of water on cold, winter days. That must have to do with my years of flying in naval aviation. But the sea won’t make any difference between who flew with the navy and who is a private pilot. Absolutely not. We all should be aware of crossing large stretches of water in a single engine aircraft. And especially in winter time, when the survival time in the water below is short. So, please read this once and read it again – every year - and it will become second nature to you. And tell me: “who doesn’t want to ‘fly another day’?”

That’s it!

Have a great next flight and……be safe!

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Note:

a. I gathered much information from various internet sites, so maybe you recognise parts of it or stumble across one of them.

b. If you have any remarks or questions concerning these true learning experiences, don’t be a stranger and please let us know on Dit e-mailadres wordt beveiligd tegen spambots. JavaScript dient ingeschakeld te zijn om het te bekijken..

Tags: Safety